Previous ships called Freedom: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m (→USS Freedom (ID-3024) (1894): Image to thumb) |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

==USS Freedom (ID-3024) (1894)== | ==USS Freedom (ID-3024) (1894)== | ||

[[Image:USSFreedom1894.jpg]] | [[Image:USSFreedom1894.jpg|thumb|right]] | ||

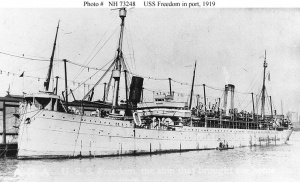

USS Freedom (ID-3024), a cargo ship, was built as Wittekind by Blohm & Voss, Hamburg, Germany, in 1894; seized by the United States Shipping Board (USSB) in 1917; renamed Iroquois, and chartered by the United States Army for use as a transport. She was renamed Freedom in 1918, acquired by the United States Navy on 24 January 1919, and commissioned the same day, Lieutenant J. C. C. Holier, USNRF, in command. | USS Freedom (ID-3024), a cargo ship, was built as Wittekind by Blohm & Voss, Hamburg, Germany, in 1894; seized by the United States Shipping Board (USSB) in 1917; renamed Iroquois, and chartered by the United States Army for use as a transport. She was renamed Freedom in 1918, acquired by the United States Navy on 24 January 1919, and commissioned the same day, Lieutenant J. C. C. Holier, USNRF, in command. | ||

| Line 18: | Line 17: | ||

Space Station Freedom was the name given to NASA's project to construct a permanently-manned earth-orbiting space station. Although approved by then-president Ronald Reagan and announced in the 1984 State of the Union Address, Freedom was never constructed or completed as originally designed, and was eventually scaled-back and converted into the International Space Station currently in operation today. | Space Station Freedom was the name given to NASA's project to construct a permanently-manned earth-orbiting space station. Although approved by then-president Ronald Reagan and announced in the 1984 State of the Union Address, Freedom was never constructed or completed as originally designed, and was eventually scaled-back and converted into the International Space Station currently in operation today. | ||

Original proposal | ===Original proposal=== | ||

In the early 1980s, with the space shuttle completed, NASA proposed the creation of a large, permanently-manned space station, which then-NASA-Administrator James M. Beggs called "the next logical step" in space. In some ways it was meant to be the U.S. answer to the Soviet Mir. NASA plans called for the station, which was later dubbed Space Station Freedom, to function as an orbiting repair shop for satellites, an assembly point for spacecraft, an observation post for astronomers, a microgravity laboratory for scientists, and a microgravity factory for companies. | In the early 1980s, with the space shuttle completed, NASA proposed the creation of a large, permanently-manned space station, which then-NASA-Administrator James M. Beggs called "the next logical step" in space. In some ways it was meant to be the U.S. answer to the Soviet Mir. NASA plans called for the station, which was later dubbed Space Station Freedom, to function as an orbiting repair shop for satellites, an assembly point for spacecraft, an observation post for astronomers, a microgravity laboratory for scientists, and a microgravity factory for companies. | ||

Reagan announced plans to build Space Station Freedom in 1984, stating: "We can follow our dreams to distant stars, living and working in space for peaceful economic and scientific gain." | Reagan announced plans to build Space Station Freedom in 1984, stating: "We can follow our dreams to distant stars, living and working in space for peaceful economic and scientific gain." | ||

Design iterations | ===Design iterations=== | ||

Following the Presidential announcement, NASA began a set of studies to determine the potential uses for the space station, both in research and in industry, in the US or overseas. This led to the creation of a database of thousands of possible missions and payloads; studies were also carried out with a view to supporting potential planetary missions, as well as those in low-earth orbit. | Following the Presidential announcement, NASA began a set of studies to determine the potential uses for the space station, both in research and in industry, in the US or overseas. This led to the creation of a database of thousands of possible missions and payloads; studies were also carried out with a view to supporting potential planetary missions, as well as those in low-earth orbit. | ||

| Line 43: | Line 42: | ||

During 1986 and 1987, various other studies were carried out on the future of the US space program; the results of these often impacted the Space Station, and their recommendations were folded into the revised baseline as necessary. One of the results of these was to baseline the Station program as requiring five shuttle flights a year for operations and logistics, rotating four crew at a time with the aim of extending individual stay times to 180 days. | During 1986 and 1987, various other studies were carried out on the future of the US space program; the results of these often impacted the Space Station, and their recommendations were folded into the revised baseline as necessary. One of the results of these was to baseline the Station program as requiring five shuttle flights a year for operations and logistics, rotating four crew at a time with the aim of extending individual stay times to 180 days. | ||

Collapse of the station program | ===Collapse of the station program=== | ||

Underestimates by NASA of the station program's cost and unwillingness by the U.S. Congress to appropriate funding for the space station resulted in delays of Freedom's design and construction; it was regularly redesigned and rescoped - between 1984 and 1993 it went through seven major re-designs - losing capacity and capabilities each time. Rather than being completed in a decade, as Reagan had predicted, Freedom was never built, and no Shuttle launches were made as part of the program. | Underestimates by NASA of the station program's cost and unwillingness by the U.S. Congress to appropriate funding for the space station resulted in delays of Freedom's design and construction; it was regularly redesigned and rescoped - between 1984 and 1993 it went through seven major re-designs - losing capacity and capabilities each time. Rather than being completed in a decade, as Reagan had predicted, Freedom was never built, and no Shuttle launches were made as part of the program. | ||

| Line 50: | Line 49: | ||

History records Freedom as being a failed project which lacked direction. However, by the time it was cancelled, the program had a firm plan, design of most components (with the notable exception of the Crew Return Vehicle) was finalised, and a large amount of flight hardware had been constructed. Had political support remained, it is likely that Freedom would have been launched in the same timeframe as the ISS, and reach a complete (four-man) configuration around 2003-5. | History records Freedom as being a failed project which lacked direction. However, by the time it was cancelled, the program had a firm plan, design of most components (with the notable exception of the Crew Return Vehicle) was finalised, and a large amount of flight hardware had been constructed. Had political support remained, it is likely that Freedom would have been launched in the same timeframe as the ISS, and reach a complete (four-man) configuration around 2003-5. | ||

Conversion to the International Space Station | ===Conversion to the International Space Station=== | ||

In 1993, the administration of President Bill Clinton announced the transformation of Space Station Freedom into the International Space Station (ISS). Then-NASA-Administrator Dan Goldin supervised the addition of Russia to the project. To accommodate reduced budgets, the station design was scaled-back from 508 to 353 square feet (47 to 33 | In 1993, the administration of President Bill Clinton announced the transformation of Space Station Freedom into the International Space Station (ISS). Then-NASA-Administrator Dan Goldin supervised the addition of Russia to the project. To accommodate reduced budgets, the station design was scaled-back from 508 to 353 square feet (47 to 33 m²), the crew capacity was reduced from 7 to 3, and the station's functions were reduced. | ||

==USS Freedom (LCS-01)== | ==USS Freedom (LCS-01)== | ||

[[Image:USSFreedom2005.jpg|300px|left]] | |||

USS Freedom (LCS-01), a Freedom-class littoral combat ship, was the third ship of the United States Navy to be named for the condition of being free from slavery, detention, oppression, or other restraints. The contract to build her was awarded to Lockheed Martin 's Marinette Marine shipyard in Marinette, Wisconsin in May 2004 and her keel was laid down on 2 June 2005. She was sponsored by Birgit Smith, the widow of United States Army Sergeant 1st Class Paul Ray Smith, who posthumously earned the Medal of Honor in Operation Iraqi Freedom. | USS Freedom (LCS-01), a Freedom-class littoral combat ship, was the third ship of the United States Navy to be named for the condition of being free from slavery, detention, oppression, or other restraints. The contract to build her was awarded to Lockheed Martin 's Marinette Marine shipyard in Marinette, Wisconsin in May 2004 and her keel was laid down on 2 June 2005. She was sponsored by Birgit Smith, the widow of United States Army Sergeant 1st Class Paul Ray Smith, who posthumously earned the Medal of Honor in Operation Iraqi Freedom. | ||

Freedom is the first of two dramatically different LCS seaframes being produced; the other (unnamed as of 2005) is under construction by General Dynamics's Bath Iron Works in Bath, Maine. | Freedom is the first of two dramatically different LCS seaframes being produced; the other (unnamed as of 2005) is under construction by General Dynamics's Bath Iron Works in Bath, Maine. | ||

==USS Freedom== | ==USS Freedom== | ||

Prototype of the Freedom Class of Federation starship in the 2360s. | Prototype of the Freedom Class of Federation starship in the 2360s. | ||

{{WikipediaContent}} | |||

[[Category:USS Freedom]] | |||

Latest revision as of 00:57, 21 September 2007

| USS Freedom-A | ||

|---|---|---|

DECOMMISSIONED | ||

| ||

NOTE: In need of editing - Salak

USS Freedom (ID-3024) (1894)

USS Freedom (ID-3024), a cargo ship, was built as Wittekind by Blohm & Voss, Hamburg, Germany, in 1894; seized by the United States Shipping Board (USSB) in 1917; renamed Iroquois, and chartered by the United States Army for use as a transport. She was renamed Freedom in 1918, acquired by the United States Navy on 24 January 1919, and commissioned the same day, Lieutenant J. C. C. Holier, USNRF, in command.

Freedom was assigned to the Cruiser and Transport Force, and after overhaul at New York, sailed on a voyage to St. Nazaire, France, and return. The cargo ship made two more voyages to France, each to Brest, with a visit to Norfolk, Virginia, between trips. She arrived at Hoboken, New Jersey, on 5 September 1919, and was assigned to duty in the 3rd Naval District. Freedom was decommissioned at New York on 23 September 1919 and returned to the USSB the same day.

USS Freedom (1940)

The second Freedom was a non-commissioned auxiliary schooner that served from 1940 to 1962.

Space Station Freedom (Became ISS)

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/2/25/Space_station_freedom.jpg

Space Station Freedom was the name given to NASA's project to construct a permanently-manned earth-orbiting space station. Although approved by then-president Ronald Reagan and announced in the 1984 State of the Union Address, Freedom was never constructed or completed as originally designed, and was eventually scaled-back and converted into the International Space Station currently in operation today.

Original proposal

In the early 1980s, with the space shuttle completed, NASA proposed the creation of a large, permanently-manned space station, which then-NASA-Administrator James M. Beggs called "the next logical step" in space. In some ways it was meant to be the U.S. answer to the Soviet Mir. NASA plans called for the station, which was later dubbed Space Station Freedom, to function as an orbiting repair shop for satellites, an assembly point for spacecraft, an observation post for astronomers, a microgravity laboratory for scientists, and a microgravity factory for companies.

Reagan announced plans to build Space Station Freedom in 1984, stating: "We can follow our dreams to distant stars, living and working in space for peaceful economic and scientific gain."

Design iterations

Following the Presidential announcement, NASA began a set of studies to determine the potential uses for the space station, both in research and in industry, in the US or overseas. This led to the creation of a database of thousands of possible missions and payloads; studies were also carried out with a view to supporting potential planetary missions, as well as those in low-earth orbit.

In April 1984, the newly-established Space Station Program Office at Johnson Space Center produced a first reference configuration; this would serve as a baseline for further planning. The chosen design was the "Power Tower", a vertical keel (with reference to the Earth) with a cluster of five modules at the lower end and a set of articulated solar arrays at the upper end. It also contained a servicing bay.

In April 1985, the program selected a set of contractors to carry out definition studies and preliminary design; various trade-offs were made in this process, balancing higher development costs against reduced long-term operating costs. In March 1986, the System Requirements Review modified the configuration to the "Dual-Keel" design, which moved the modules to the central truss - placing them at the centre of gravity, providing a better microgravity environment - and increased the amount of truss structure, with two large "keels". As the international involvement became more organised, the number of US lab modules was reduced from two to one, taking into consideration the provision of space in the European and Japanese modules.

Following this, the design was extensively "scrubbed" to remove inefficiencies; this led to a large number of subsystems being revised or removed, the deferral of plans for an Orbital Maneuvering Vehicle to be based at the station, and the use of only a single habitation module for a crew of eight.

In May 1986, NASA produced a report which had studied the assembly sequence with the intent of providing early "man-tended" capacity - in other words, ensuring that at an early stage, despite the Station not being able to support a crew, research work could be carried out by occasional visiting Shuttle flights.

Following the Challenger accident, a Critical Evaluation Task Force was set up to reassess the validity and safety of the current Station design. Whilst this validated the use of the Dual-Keel design, post-Challenger safety concerns did lead to changes in the assembly plans, as well as assorted minor changes. Johnson Space Center had previously expressed misgivings about the amount of EVA work needed to assemble the Station, which was addressed, as was the Shuttle-payload reductions stemming from safety improvements post-Challenger.

In September 1986, a major cost review of the program was undertaken from the post-Challenger baseline; this was intended to ensure that NASA had a solid basis for its commitment to cost and schedule. The review found that the total development cost for the Dual-Keel configuration would cost $18.2 billion (in FY1989 dollars), and a slip in the first-element launch (FEL) date from January 1993 to January 1994.

At the same time, NASA carried out a study into new configuration options to reduce development costs; options studied ranged from the use of a Skylab-type station to a phased development of the Dual-Keel configuration. This approach involved splitting assembly into two phases; Phase 1 would provide the central modules, and the transverse boom, but with no keels. The solar arrays would be augmented to ensure 75kW would be provided, and the polar platform and servicing facility were again deferred. The study concluded that this was viable, reducing development costs whilst minimising negative impacts, and it was designated the Revised Baseline Configuration. This would have a development cost of $15.3 billion (in FY1989 dollars) and FEL in the first quarter of 1994. This replanning was endorsed by the National Research Council in September 1987, which also recommended that the long-term national goals should be studied before committing to any particular Phase 2 design.

During 1986 and 1987, various other studies were carried out on the future of the US space program; the results of these often impacted the Space Station, and their recommendations were folded into the revised baseline as necessary. One of the results of these was to baseline the Station program as requiring five shuttle flights a year for operations and logistics, rotating four crew at a time with the aim of extending individual stay times to 180 days.

Collapse of the station program

Underestimates by NASA of the station program's cost and unwillingness by the U.S. Congress to appropriate funding for the space station resulted in delays of Freedom's design and construction; it was regularly redesigned and rescoped - between 1984 and 1993 it went through seven major re-designs - losing capacity and capabilities each time. Rather than being completed in a decade, as Reagan had predicted, Freedom was never built, and no Shuttle launches were made as part of the program.

By 1993, Freedom was politically unviable; the administration had changed, and Congress was tiring of throwing yet more money into the station program. In addition, there were open questions over the need for the station - redesigns had cut most of the science capacity by this point, and the Space Race was well and truly dead with the fall of the Soviet Union. NASA presented several options to President Clinton; even the most limited of these was still seen as too expensive. In June 1993, a bill to cancel the Station program failed by one vote in the House of Representatives, 215-216; that October, a meeting between NASA and the Russian Space Agency agreed to the merger of the projects into the International Space station.

History records Freedom as being a failed project which lacked direction. However, by the time it was cancelled, the program had a firm plan, design of most components (with the notable exception of the Crew Return Vehicle) was finalised, and a large amount of flight hardware had been constructed. Had political support remained, it is likely that Freedom would have been launched in the same timeframe as the ISS, and reach a complete (four-man) configuration around 2003-5.

Conversion to the International Space Station

In 1993, the administration of President Bill Clinton announced the transformation of Space Station Freedom into the International Space Station (ISS). Then-NASA-Administrator Dan Goldin supervised the addition of Russia to the project. To accommodate reduced budgets, the station design was scaled-back from 508 to 353 square feet (47 to 33 m²), the crew capacity was reduced from 7 to 3, and the station's functions were reduced.

USS Freedom (LCS-01)

USS Freedom (LCS-01), a Freedom-class littoral combat ship, was the third ship of the United States Navy to be named for the condition of being free from slavery, detention, oppression, or other restraints. The contract to build her was awarded to Lockheed Martin 's Marinette Marine shipyard in Marinette, Wisconsin in May 2004 and her keel was laid down on 2 June 2005. She was sponsored by Birgit Smith, the widow of United States Army Sergeant 1st Class Paul Ray Smith, who posthumously earned the Medal of Honor in Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Freedom is the first of two dramatically different LCS seaframes being produced; the other (unnamed as of 2005) is under construction by General Dynamics's Bath Iron Works in Bath, Maine.

USS Freedom

Prototype of the Freedom Class of Federation starship in the 2360s.